Disclaimer: This is a personal reflection article and does not claim to be based on targeted primary data collection on the topic. My reflections stem from the conversations and stories shared by women from Kashmir during my travels across the region. While deriving from the stories, I only seek to provide a broader framework for my argument and will not be revealing the identity or details of the stories that have been shared with me through bonds of trust. I am blessed to have this opportunity to provide a safe space to my sisters and mothers in Kashmir and wish to ensure that I don’t misrepresent or misinterpret their voices in any way. I seek to offend none and only write to advocate for evolving more safe spaces to build the context for a gender empowerment narrative in the region that is supported by the notion of cultural agency, suited to the spirit of “Kashmiriyat” as the women themselves see it through their own stories.

Having said that, this article forms the basis of my primary assessment as a peace-builder for more intended research efforts on the topic in the future. I wish to clearly mention at the very outset that I write this article as an outsider, a Bengali woman hailing from a matriarchal cultural setting, seeking to understand the context for designing gender empowerment focused policy inputs in Jammu and Kashmir. I am still learning and would love to receive feedback and alternative perspectives on the topic.

Introduction

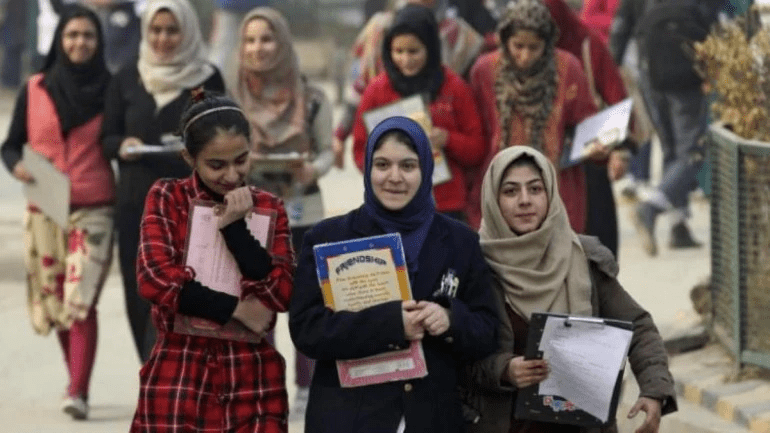

Stories have always been my most preferred form or mode of getting to know and understand a new culture. As a Bengali woman working to support research on a number of development goals in Jammu and Kashmir, I always knew that local stories and experiences of the people would be invaluable for me to build my sense of cultural sensitivity to help me contextualize my work with the intention to better suit the needs of the people on the ground. It is in this context that I write to present a preliminary observation pertaining to an important focus area for my work. I write today to outline my assessment of the lack of and consequent need for safe spaces to bring to life a narrative based on women’s stories and experiences to build the foundation for gender empowerment initiatives in Jammu and Kashmir.

Generous Warmth, Pain and Silence, the Womb for the birth of Power

It was during my visits to many a home while on my field trip across Kashmir( I have only travelled to a limited extent and have much more to see) that I first realized how the world-renowned hospitality of Jammu and Kashmir is a tradition held in place by women within the community. They are the ones who invite you in and give you a sense of home. They are the ones who ensure that the essence of their culture seeps into your veins through the cheerful conversations at the hearth over steaming mugs of salty tea and bread, the ones who make that effort to go that extra mile to help you acclimatize and also offer you with a bountiful heart, their home, to help you settle down. I have lost count of how many homes have opened up their doors to invite me to stay as a daughter. This is the tradition, the best representation of treating the guest as no less than a blessed encounter. As I chatted with many a woman in many of the homes of my team members, their relatives and also people I met on the way, it struck me as truly interesting how Kashmiris welcomed people from all over the world to experience home in their land as if they were their kin but at the same time struggled to trust that they had a safe space as a reciprocal gesture from the world out there that seems to have forgotten them. How much pain and a feeling of being forsaken could have pushed the Kashmiri people to love and embrace the world without any reciprocal expectation in return. “Outsiders are all the same didi. They first give you hope and then disown you.” These were the words of a young girl who never failed to tell me how much she loved spending time with me. There seemed to be a trauma of betrayal, a general sense of deep hurt. This made me wonder if as an outsider, I had something to offer besides my research-related skills. Maybe I could offer a strategy to provide a safe space for stories untold and voices unheard of for years. Maybe I could be an ear for the voices of women to find their power as important stakeholders in defining their culture that they already do, albeit silently. This young girl eventually shared with me her story and experiences and how she rose out of feelings of abandonment, exploitation and the craving for a safe space to be herself. As it stands, she wishes to be a religious educator one day in a school.

In Kashmir, as per my observations, there seems to be an evolved culture of more or less clear segregation of gender roles that is designed to suit the circumstances. The conflict has torn and highly militarized as a region as Kashmir already is, besides the history of the population struggling repeatedly due to instances of broken promises, political fall-outs and externally triggered disruptions through an ever-evolving and dynamic trend in militancy, the region naturally stands as one of the least-favourable places to even rationally consider finding a crucible of psycho-emotional safe space for heart-felt sharing and outpouring of pain, especially for women. The men are vigilant of their households( naturally so) and in the spirit of keeping their families safe, the women consciously seem to choose to facilitate the arrangement by maintaining a careful silence that is palpable but barely made visible. As a facilitator trained to read silence while listening to various stakeholders, I decided to make a conscious effort to listen and connect deeper. In some cases, stories eventually came out in cathartic outpourings and many a woman took to me as someone who they could instinctively trust to empathize with their silenced stories to some extent. It was on one of my visits to the home of a lady Police Officer that she shared her story of choosing to be a part of the State Security Structure back in the early 90s, during the heyday of the insurgency. I suddenly found myself looking at empowerment as a response to circumstances, a conscious choice that this lady had made as an 18-year-old, 30 years back, to not let uncensored violence rip apart her life or her future like it had for many others. Her two daughters today aspire to be a business lawyer and an administrator though motivated to do so from afar sheltered reality as it stands now. When this officer narrated to me her story, I witnessed her re-living the moments that shaped her choice and decision. I was taken back to the times when foreign militants from across the border would barge into homes, harass young women and stay in the homes of different people without any consideration of how the families perceived their invasive tendencies. Sometimes young women from these households would be coerced to marry the militants and then inevitably they would be left at some point with fatherless children as the militants would be neutralized at the hands of the state or some would even flee without any notice. During those days when joining the Police Force wasn’t exactly an applauded option for any young woman, this lady made the choice, supported by her family and is still serving the Police Force for over 25 years. Given this lady’s decision to join the Police Force came during the most unlikely times, despite the passage of thirty years and the militancy situation being somewhat in better control than yesteryears, you wouldn’t find many Kashmiri women coming forward to make the same choice today. Maybe there could have been a different outcome? Maybe there could have been more women making such choices in the face of dire uncertainties and struggling it out had they been aware of such an existing story? We would never know. Interestingly, it was this lady’s two daughters who encouraged her to share, hinting to me time and again that their mother had a story that was silenced. Clearly, they derived inspiration and strength from the story and wanted me to experience the same. On probing why she wouldn’t share her story generally, I was told that it wasn’t safe to confide in people with stories of deep personal meaning and trauma. There was a sense of fear of ridicule and judgment that weighed down on the imposed silence. To me, this particular case and story opened up the possibility of an existing empowerment narrative that is already present in the valley but silenced and not studied as a factor of post-traumatic growth for women. This lady had seen much harassment, much threat and despite all odds had remained firm on her choice. Maybe there were more like her, leading the way, championing the cause of standing one’s ground and being decision-makers in their own stride. As a policy researcher, I was stunned at the potency of such stories of courage and inspiration but my conflict analysis background told me that these stories needed the optimal environment to be brought to life as lived possibilities. The silence for once appeared to me as a gestation period for the birth of power should the environment be fertile and conducive for the birthing process.

Over the period of a month as I listened deeper, I connected with women who are silently leading not only as matriarchs in households but also participating in elected posts at the behest of their menfolk to support change and the search for power by the community to be decision-makers and masters of their own fate. Even in public posts, women taking up reserved seats are mostly seen to be supportive and silent in terms of addressing their own priorities and are mostly guided by their menfolk in deciding on community priorities in their official capacities. As I travelled,I listened further to stories of women who have lost their dear ones to the militancy, witnessed torture of their family members, suffered lasting injuries as a result of the militancy and yet fought on to emerge wiser, stronger, shaping generations and thus the community and culture. Curious eyes, giggles and hushed murmurs followed my footsteps everywhere as I met women from the cities, towns and villages. I felt the silence everywhere but could earn only limited trust and opportunity to open up the safe space for story sharing. As the lady officer’s story inspired her daughters to look at the cultural agency of women in their context in an enabling light, maybe allowing such stories to be shared could inspire future generations of women to rethink possibilities for becoming a part of an existing empowerment narrative rather than a borrowed one that is usually peddled in mainstream discourses. Maybe such stories can encourage women to decide for themselves that their roles are not defined by or limited to the conflict-driven idea of “safety” or “acceptability” and that local women have already laid the first steps to re-imagining empowering possibilities.

Measuring Possibilities in Story-sharing: Recommended Actions

Compassionate dialogue circles with the aid of trained facilitators and supportive psychologists could go a long way to bring out this narrative that is otherwise suppressed and soon endangered to be lost beyond recovery. These narratives can in turn support the cause of women making a conscious choice to welcome gestures by advocates of gender equality to create a space for empowering opportunities. Opportunities are after all only useful when the target group finds it feasible and are encouraged to use such opportunities to their benefit as a mark of conscious choice. Women need stories to thus frame a narrative that supports their sense of cultural agency to negotiate against the seeming trend. In terms of the trend to silently support, there could evolve a way to create a culture of psycho-emotional safety and protection of privacy while developing the narrative from real-life stories. Anonymity and confidentiality in story sharing circles and research documentation could be one way of ushering in trust to support the process.

Conclusion

In Kashmir, the silence of women appears to be a choice that is steeped in culturally adaptive motive, a trauma driven response and an attempt to foster the remains of a culture that is still seeking to stay rooted in the spirit of coexistence and community. As one young woman and my peer mentioned; in her opinion, women here can never make it far while living in the region and they can barely do much. I found myself instinctively responding to her exasperation with the following words, “It is the contrary actually. Hadn’t it been for the silent choice to be the sponge and the weaving net of the cultural fabric that you women have provided for generations, there would be no Kashmir. Maybe it is time to write that story together.”

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.