For a long time, we have produced more than we can consume and dispose of far more than the earth can renew and replenish. The fast fashion industry is one of the biggest contributors to resource depletion. It has grown exponentially over the past two decades and still continues to register growth unabatedly. The industry contributes significantly to the mass wastage that has accumulated in landfills and dumping yards around the world.

This article is an attempt to unearth the nuances and subtleties of the fast fashion industry and the repercussions due to its mass consumption.

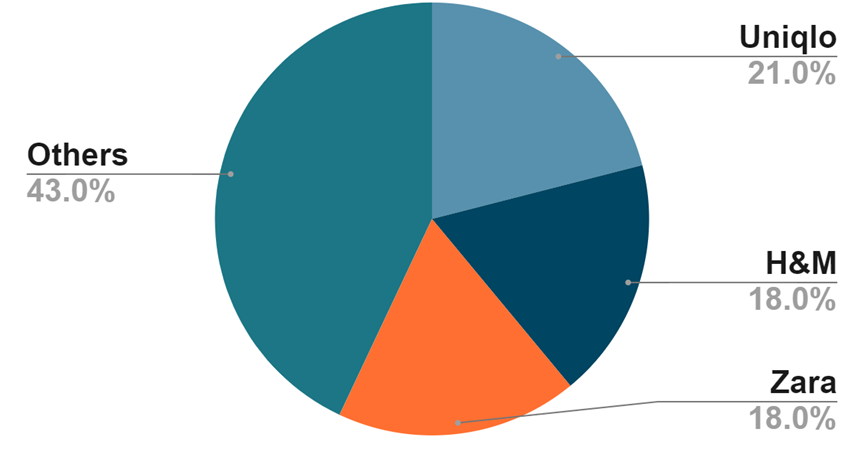

Fast fashion refers to clothing designs that move quickly from the catwalk to stores in order to capitalize on trends. The collections are frequently inspired by styles seen on the runways of Fashion Week or worn by celebrities. Fast fashion allows mainstream consumers to get the hottest new look or the next big thing at a low cost. Zara, H&M Group, UNIQLO, GAP, Forever 21, Topshop, Esprit, Primark, Fashion Nova, and New Look are among the major players in the fast-fashion market. According to a survey, Uniqlo (21%), H&M (18%), and Zara (18%) are the world’s most popular fast-fashion retailers.

Fast fashion as new normal

In modern societies, fast fashion represents the culture of instant gratification. Today’s fast fashion exploits people’s desire for new and shiny things. Fast fashion became popular due to affordability, faster manufacturing and shipping methods, an increase in consumers’ appetite for current fashion, and an increase in consumer purchasing power—particularly among young people—to satisfy the desire for instant gratification. Cost is a significant factor for consumers, particularly those in the younger age brackets. More than 60 million tonnes of clothing are now purchased each year, with this figure expected to rise to around 100 million tonnes by 2030. Accessibility is also another influencer on fast fashion’s popularity.

The fast fashion industry also provides more profits to companies. The constant introduction of new products encourages customers to visit stores more frequently, resulting in more purchases. The retailer does not replenish its inventory; instead, items that sell out are replaced with new items.

Environmental impact assessment

The environmental impact is far greater than a cursory examination of the industry reveals. Because of its low-cost materials and manufacturing methods, fast fashion contributes to pollution, waste, and planned obsolescence. The throwaway culture has steadily regressed over time. Many items are now worn only seven to ten times before being discarded. That’s a more than 35% drop in just 15 years. According to the United Nations Alliance for Sustainable Fashion, an initiative of the United Nations and allied organizations, underutilization of clothing and lack of recycling costs an additional $500 billion per year.

Clothing production depletes natural resources and generates greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to climate change. Textile manufacturing is the world’s second most polluting industry. According to the UN, the fashion industry accounts for 8-10% of global emissions, including carbon dioxide, and 20% of industrial wastewater pollution – more than aviation and shipping combined. If business as usual continues in the coming years, with no action taken to reduce fast fashion waste, the industry’s global emissions are expected to rise by 50% by 2030.

Let’s take a quick look at some figures which shows how the fashion industry is one of the biggest contributors to environmental degradation.

- Every year, the fashion industry, one of the world’s largest users of water, consumes anywhere from 20 trillion to 200 trillion liters. One pair of jeans requires 3,781 liters of water to produce. One t-shirt requires approximately 2,700 liters of water, which is enough for one person to drink for 900 days.

- 20% of all wastewater in the world is from textile dying and is highly toxic—many countries where clothes are manufactured have lax or no wastewater disposal regulations.

- Garments are a significant source of microplastics because so many are now made of nylon or polyester, which are both durable and inexpensive. Microplastic fibers from clothing enter the ocean via sewage systems, amounting to approximately 500,000 tons—roughly 50 billion plastic bottles.

- Poorly crafted garments do not age well, but they cannot be recycled because they are primarily (over 60%) made of synthetics. As a result, when they are discarded, they mold for years in landfills. Every year, 92 million tonnes of textile waste are generated.

Besides this, most of the fashion’s environmental impact comes from the use of raw materials:

- Cotton for the fashion industry consumes approximately 2.5% of the world’s farmland. Cotton farming uses 4% of all nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers used globally, 16% of all insecticides, and 7% of all herbicides.

- Synthetic materials such as polyester use an estimated 342 million barrels of oil per year.

- While clothing manufacturing processes such as dying use 43 million tonnes of chemicals per year.

Moving beyond Fast Fashion

It is difficult to completely avoid products manufactured by fast fashion companies; however, it is not impossible. One issue is consumerism and price; many people cannot afford the actual products that fast fashion imitates but are obsessed with the latest trends. Apart from resisting consumerism, one can look into the brands they like to see if they use sustainable processes. Switching to sustainable clothing is the need of the hour.

Sustainable clothing is frequently made from organic fabrics that decompose easily. Natural dyes are used to color the fabrics, and no chemicals are present in the clothing. Because everything used is natural and organic, it is beneficial to the skin as it helps to avoid rashes and skin infections. Eco-friendly fabrics and accessories have a long lifespan and can be repurposed and reused. As per the United Nations Alliance for Sustainable Fashion, a sustainable approach would greatly assist in overcoming environmental challenges, such as reducing the industry’s waste stream, water pollution, and GHGs.

The most effective way to reduce environmental degradation is to raise awareness about the huge benefits of sustainable clothing. Most people are unaware of fast fashion’s social and environmental impact; only by raising awareness will companies producing these products be held accountable. According to YouGov, a consumer and data insights consultancy, more than 8 in 10 Indian consumers are interested in purchasing sustainable fashion items. It is desirable to have positive communication about sustainable fashion and incentives. 41% of respondents say they are more likely to buy sustainable products if they are well informed about the benefits and consequences of doing so. Similarly, 41% believe that incentives in the form of reward points would encourage them to purchase more environmentally friendly products. The survey further argues that celebrity endorsement of sustainable fashion would prompt more than a fifth (23%) of respondents to purchase sustainable products.

Furthermore, research — both academic and industrial — plays a significant role in achieving these and other goals. For instance, researchers could begin by assisting in the provision of more accurate estimates of water use. It must be possible to reduce the range of 20 trillion to 200 trillion liters of water. Additionally, there is work to be done to improve and expand textile recycling. Another area of study can be determining how to persuade consumers and manufacturers to change their behavior. This is already a hot topic in the social and behavioral sciences.

The government and the fashion industry must work together to promote positive attitudes and incorporate sustainability into policies and practices. The time is right to talk about sustainable fashion because the government is establishing seven mega textile parks to boost the industry’s global competitiveness. Including sustainability in the value chain would prepare the industry for the future and give it a competitive advantage globally.

Conclusion

Fast fashion creates a slew of toxic by-products that make it more problematic than beneficial. The industry contributes immensely to greenhouse gas emissions that lead to climate change, pesticide pollution, water pollution, and massive waste production. Given the magnitude of the ecological challenges, all key stakeholders, from governments to businesses and NGOs to individual consumers, must pursue a multi-pronged green approach individually and collectively in order to avoid an ecological crisis. An amalgamation of precision and coordination in policymaking should be prioritized. There is a need to talk about sustainable fashion. The hazardous environmental cost of a flashy new wardrobe must be addressed immediately, on a large scale.

References:

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fast-fashion.asp#:~:text=Fast%20fashion%27s%20benefits%20are%20affordable,low%20wages%2C%20and%20unsafe%20workplaces

- https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-60382624

- https://www.blabel.in/blogs/hemp-lovers/how-sustainable-fashion-can-help-us-move-beyond-fast-fashion#:~:text=It%20Generates%20Less%20Waste%20%26%20Takes%20Care%20Of%20The%20Environment&text=This%20way%2C%20we%20create%20less,massive%20ocean%20of%20waste%20reduction

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/development-chaupal/making-sustainability-fashionable/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-02914-2

- https://earth.org/statistics-about-fast-fashion-waste/#:~:text=1.,on%20landfill%20sites%20every%20second

- https://www.panaprium.com/blogs/i/fast-fashion-popular

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.