Climate change, once perceived as a distant spectre, now manifests as a pressing local and global crisis. The intensification of extreme weather events, escalating greenhouse gas emissions, and burgeoning socio-economic disparities amplify the urgency of addressing climate-related challenges. India, positioned as one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, grapples with the dual imperative of fostering development while safeguarding environmental sustainability.

This article explores how fairness in dealing with climate issues is important in India. It talks about how laws and court rulings play a role, and why everyone working together is crucial. By looking at how climate change affects people’s rights according to the constitution, it shows why policies, laws, and community efforts are needed to reduce its harmful effects and make society fairer and stronger.

John Rawls, in his book Theories of Justice, aptly describes justice as “a virtue of social institutions and the validity of systems of thought.” According to this definition, if laws and institutions are not just, they should be removed, no matter how well-organized and efficient they are. A similar argument can be advanced when contextualizing the discourse on climate justice. Climatic aberrations or environmental crises are no longer endemic to specific regions; they are now transnational and have engulfed the entire world.

Recently, the Supreme Court of India passed its judgment in a case titled M.K. Ranjitsinh & Ors versus Union of India & Ors regarding the protection of two critically endangered bird species on the IUCN Red List: the great Indian bustard (GIB) and the lesser florican. While safeguarding the habitat of these endangered birds, the Supreme Court recognized that climate change impacts the constitutional right to live. Therefore, in advancing this historic judgment, the Supreme Court argued that people have a right to be free from the adverse effects of climate change, as enshrined under Articles 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. This judgment has extended the definition and interpretation of Article 14 (Right to Equality) and Article 21 (Right to Life and Right to a Pollution-Free Environment).

Climate change is not just a global issue but a local one as well. Floods have become more frequent and intense, rainfall patterns are changing, and heat waves across the globe are posing serious health threats. The erratic behaviour of extreme weather patterns, coupled with embedded spatial and structural inequalities, is swiftly changing the habitats of multiple species. A 2022 United Nations report predicts that developing countries will need $300 billion annually by 2030 to tackle climate change. The World Bank warns that by 2030, over 132 million people could face extreme poverty. Marginalized populations are at particular risk, impacting food security, water, health, biodiversity, and culture.

In yet another startling study, published by Dartmouth in the journal Climate Change in 2022, it was found that five nations cumulatively caused $6 trillion in global losses due to warming from 1990 to 2014. The study computed the damage caused by major emitters of greenhouse gases to other countries. Along with the US, China also led this list, with a combined loss of $1.8 trillion during the stated period. India is also facing the brunt of climate change.

Climate Justice and India

India has witnessed many climatic aberrations in recent years. As a fast-developing country, it must balance growth and environmental sustainability. In 2019, India became the third-highest annual emitter of greenhouse gases in the world, overtaking the European Union. The first two positions are held by the US and China. The Dartmouth study reveals that India’s emissions are responsible for causing an estimated loss of more than $500 billion over the 25 years under consideration.

A 2023 report by the Delhi-based think tank Centre for Science and Environment indicated that India experienced extreme weather events almost every day in the first nine months of the year, resulting in nearly 3,000 deaths. As of July 23, 2023, statistics from the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare showed that heat waves killed 264 people across 14 states between 2015 and 2023. Extreme rainfall has also increased significantly. A study published in the journal Nature Communications in 2017 revealed that extreme rain events over central India tripled between 1950 and 2015, affecting about 825 million people, leaving 17 million homeless, and killing about 69,000.

Several studies, including Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, have indicated that global warming will put an increasing number of Indians at risk in the coming years. Indigenous communities in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands depend on nature, and their relationship with nature may be tied to their culture or religion. The destruction of lands and forests or their displacement from their homes may result in a permanent loss of their unique culture. In these ways, too, climate change may impact the constitutional guarantee of the right to equality (Article 14).

Constitutional Provisions and Landmark Decisions:

The introductory part of the Indian Constitution, the Preamble, underlines the need to ensure a decent standard of life and a pollution-free environment as necessary conditions. Article 48A states that the State shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife of the country. This article was added by the 42nd Amendment in 1976, placing an obligation on the State to protect the environment and wildlife.

One of the pioneering and historical cases was M.C. Mehta vs Union of India (Oleum Gas Leakage Case). In this case, the Supreme Court (SC) treated the right to a pollution-free environment as part of the Fundamental Right under Article 21 (Right to Life). Thus, the right to live in a healthy environment was declared to be part of Article 21 of the Constitution. A similar argument was further advanced in M.C. Mehta in the Taj Mahal case. The SC acknowledged that apart from chemicals, socio-economic factors also influenced the degradation of the Taj Mahal. Furthermore, the judgment reads that the lives of people in its catchment area are vulnerable. With such decisions, the Supreme Court has expanded the scope of Article 14 and Article 21 to underline the need to protect lives and livelihoods in the face of climate change. This will help in accentuating efforts to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change.

It is imperative to understand that the impacts of climate change are numerous. Climate change and environmental degradation lead to acute food and water shortages, with poorer communities suffering more than the wealthy. Forest dwellers, tribal, and indigenous communities face a higher risk of losing their homes and culture due to climate change compared to other communities. Furthermore, climate change impacts human rights such as the right to health, indigenous rights, gender equality, and the right to development.

An important deterrent came into existence with the Indian Council of Enviro-Legal Action vs Union of India case of 1996. In India, the ‘polluter pays principle’ was defined and applied for the first time in this case. The Supreme Court held that any industrial firm engaged in dangerous substances shall be liable to pay for the damages caused by such operations. According to the Supreme Court, ‘the absolute liability for harm to the environment extends not only to compensating the victims of pollution but also to covering the cost of restoring environmental degradation’.

In addition to this, the Government of India initiated the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) in 2008 as one of the 8 national missions. It reiterates its commitment to devising impactful strategies for climate change adaptation and mitigation, energy efficiency, and natural resource conservation while safeguarding the interests of vulnerable sections of its population. In line with this, Greenpeace India’s climate justice campaign advocates urgent climate mitigation and adaptation by collaborating with communities. It advocates that it is necessary to delve into the historical experiences of local communities, document the financial impacts on diverse socioeconomic classes, acknowledge caste and class roles in natural resource distribution, and then align policies with these intricate realities. Various states in India are vulnerable to climate disasters. Along with this, tourist places are facing a rising tourist footprint affecting their ecology.

The disastrous floods in Kerala in 2018 affected over a million tourists and demonstrated the vulnerability of tourist hotspots to climate-related disasters, with the state suffering economic losses of up to $4.4 billion. Urban areas such as Delhi, Jaipur, Mumbai, and Hyderabad are becoming ‘heat islands’, with temperatures remaining higher for longer periods.

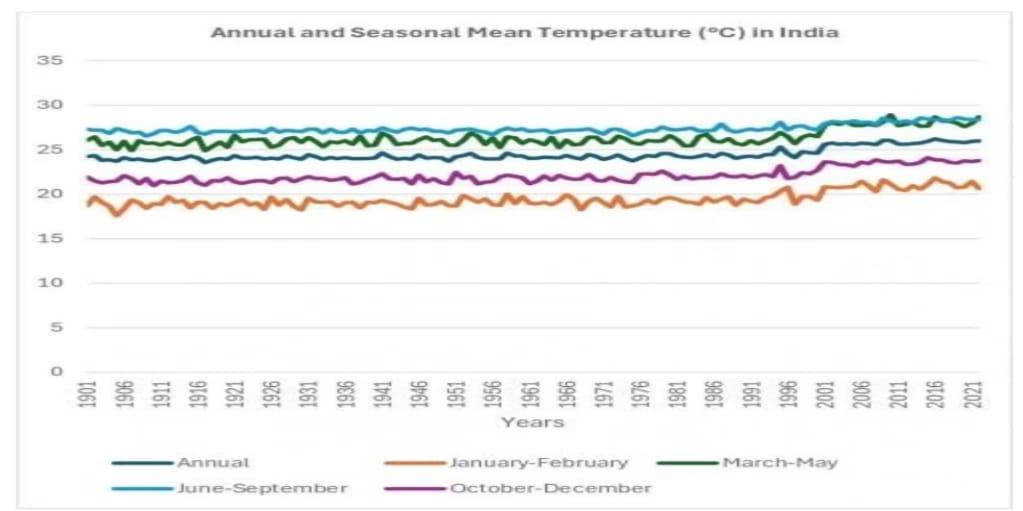

Source: IndiaStat

Way forward

Historically, industrialization and colonialism have exacerbated emissions inequities. Developed countries have experienced phenomenal growth both economically and technologically. They have access to better technology and are more efficient in adapting to and mitigating the impacts of climate change. However, the adverse impacts of climate change are becoming more discernible in the Global South. In fact, there is a greater need for climate justice in the Global South, which is facing grave consequences of climate change.

When we contextualize this in the Indian scenario, we find that around 75% of Indians depend on the sustainable use of natural resources like agriculture and forestry for their subsistence. However, they face the greatest climate vulnerabilities. According to Kashwan, climate policies in India are inequitable and disproportionately benefit certain sections and classes, especially the urban middle/upper classes and corporate lobbies. These policies discriminate against marginalized rural populations. He attributes this to the exclusionary policymaking processes, which are dominated and shaped by vested interests, perpetuating social inequalities of caste, gender, and class.

According to Kashwan, the solution to these crises lies in transformative bottom-up change. These changes should be driven by grassroots movements at local, regional, and national levels. He emphasizes giving voice to indigenous and rural communities while decentralizing governance to create context-specific solutions. Additionally, there is a need to reconstitute and reframe climate action through the lens of social justice and equity so that marginalized voices are adequately represented.

Recommendations

Re-examination and Reformation of Policy Processes: To guarantee the inclusive representation of underrepresented voices, such as those of indigenous communities and rural populations, policy-making processes should be revisited and reformed.

Decentralization of Policy Plans and Actions: There is a need to decentralize locally relevant climate adaptation plans that consider the specific ecological needs and cultural settings of various communities and regions in India.

Recognition of Intersectional Impacts: Climate justice requires recognizing the disproportionate effects of climate change on marginalized groups and using climate policies to address the intersecting disparities of caste, gender, and class.

Protection and Promotion of Community Rights: Climate justice warrants the protection and promotion of differentiated community rights and collective ownership over natural resources against corporate exploitation. Specific community-driven initiatives aimed at climate resilience should also incorporate indigenous ecological knowledge and practices.

Representation: Climate justice mandates that the voices of all groups and sections of society across the globe should be adequately represented.

Redistribution: The fundamental objective of justice is the redistribution of resources to achieve equity. The Global South is heavily facing the repercussions of climate injustices historically perpetrated by developed countries. Therefore, the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities should be practised to mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change.

Conclusion

Climate justice seeks fairness in the distribution of burdens and benefits of climate change among countries. Furthermore, both mitigation and adaptation are required. This is possible only through coordination, cooperation, and building consensus. Additionally, developed countries must fulfil their obligations under Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR).

Strategies such as mitigation seek to reduce the human impact on the environment by decreasing greenhouse emissions. On the other hand, the adaptation approach is more focused on tackling the challenges that climate change is bringing about.

Climate action plans must be embedded in inclusion, justice, and equity. These principles can unlock transformative outcomes that transcend carbon reduction targets.

Promoting a circular economy and sustainable lifestyles should be the goal of policy institutes and organizations. They can highlight initiatives aimed at minimizing waste, boosting recycling rates, and developing unique packaging designs that encourage the circular economy.

Finally, technology should be designed to meet the needs of specific regions. By blending technology within a geographical and cultural setting, the applicability of technology in those local conditions will increase. Furthermore, sharing waste management and Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) practices should be given precedence. Hence, climate justice is fundamental to the very existence of living creatures, emphasizing inclusion, equality, equity, and justice.

References:

-

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09644016.2023.2216102?scroll=top&needAccess=true

-

-

-

https://revolve.media/features/climate-action-and-justice-india

-

-

-

-

https://www.epw.in/journal/2024/13/book-reviews/liberatory-praxis-and-climate-justice-discourse.html

-

-

-

https://www.undp.org/india/publications/towards-climate-justice-examples-across-india

-

https://ijlmh.com/paper/climate-change-and-environmental-justice-in-india/

-

-

-

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.