The change in global precipitation, increasing surface temperatures, receding of glaciers, and unseasonal snowfall are all manifestations of climate change, posing an unprecedented threat to mankind. Pastures have turned into barren lands. Due to a decrease in rainfall over the past 20 years, the transhumance calendars have shifted and rainy seasons are not predictable. The livelihood and existence of marginalized communities comprised of Gujjars and Bakarwals are no exception to this.

The Gujjars and Bakarwals are nomadic tribes who live in the Himalayan mountains of South Asia, from the Pir Panjal Range to Hindukush and Ladakh. They can be found throughout the Kashmir region between India and Pakistan, as well as in Nuristan Province in northeast Afghanistan.

Jammu and Kashmir has 12 Schedule Tribes. The Union Territory’s total population of Schedule Tribes is 14,93,299, according to the 2011 Census. Gujjar is the most populous of the 12 Schedule Tribes, with a population of 9,80,654 whereas Bakerwals constitute the third-largest tribe, with a population of 1,13,198. The third-largest community in the Union territory is made up of the nomadic Gujjar and Bakerwal tribes.

Social and Economic Profile

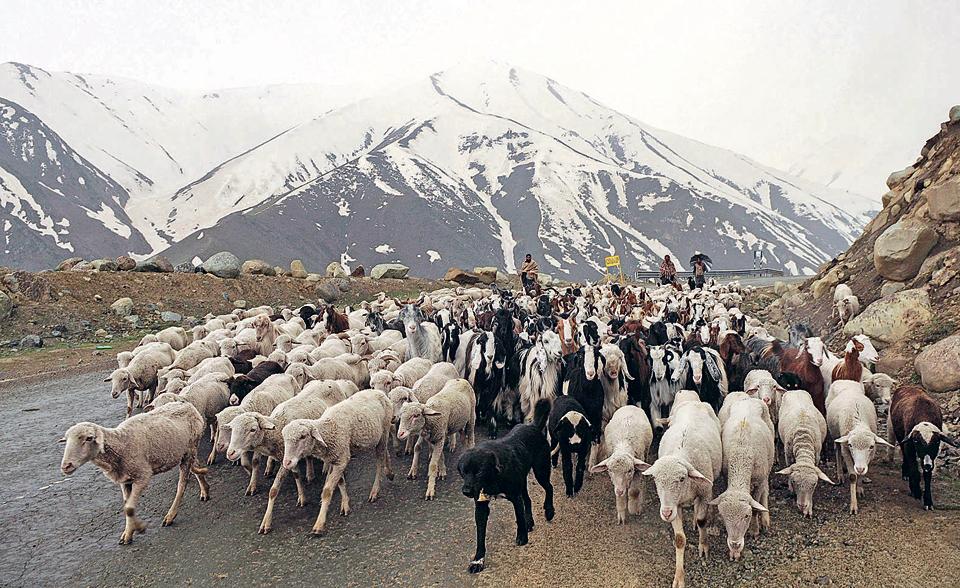

Over 5,00,000 of the total population of Gujjars and Bakarwals rear sheep, buffalo, cows, goats, and horses for their survival. They migrate from one place to another with their herds on a seasonal basis. Ajjadh, Dohdhi Gujjars, Banhara Gujjars, and Van-Gujjars are some of the names given to the Gujjars. Those who raise goats and sheep are known as Bakarwals among the Gujjars. “Bakarwal” means “high-altitude goatherd/shepherd”.

The Bakarwals alternate with the seasons between high and low altitudes in the Himalayan hills. They migrate biannually between the montane Himalayan pastures of Kashmir and Ladakh in the summer and the plains and Peer-Panjal ranges of Jammu in the winter. Bakarwal nomads set up and maintain watering holes and clear away dry/dead plant matter in the Jammu hills during the winters as part of their ecological contribution to the region. The primary source of income for Gujjars and Bakarwals is livestock and livestock-related products in which the cyclical migration process ensures that their flock has access to pastures all year.

The seasonal movement has been witnessing change over time. The Bakarwals’ pastoral economy is primarily based on the use of vast pastures. The availability of pastures is markedly seasonal in nature, while snow covers the mountains in the north, pastures are available in the south throughout the winter. However, by late April, the winter pastures have been depleted, while melting snow in the north has resulted in green and lush pastures. As a result, the availability of pastures during a specific time of year distinguishes both the winter and summer zones. This results in an oscillation between summer and winter zones; as summer approaches, the drying up of the pastures in the south signals the time to move the animals to higher or cooler altitudes in the north. Bakarwals travel through Pir Panjal’s nine major mountain passes to reach their summer destinations. The main mountain passes are Nandangali and Pir ki Gali, which account for more than 70% of the Bakarwals’ seasonal movement. By the end of April, they have mostly traversed these passes.

Vulnerability to Livelihood

According to the Economic Survey of J&K, 2020 more than 42% of the population of Scheduled Tribes, of which the majority are Gujjars and Bakarwals, lived below the poverty line. It further highlighted that these communities are highly vulnerable to climate change. Climate change has forced them to cross one month ahead of schedule due to the unusually warm march. Since in march sheep and goats give birth, the sudden change in temperature has an impact on the newborn livestock in their winter pastures, which is a major source of income for the community. According to a survey, the Bakarwals have been forced to move early to summer pastures due to a new and pressing problem of water and fodder scarcity. Bakarwals are forced to graze in pastures that do not provide adequate grazing due to the rapid melting of snow. Temperatures in their summer pastures are too low due to the early arrival, which has impacted their livestock population. As a result of the comparatively higher temperatures in March and the lack of rainfall, they are forced to move earlier, affecting their production. The herds’ mortality rate has increased in recent years. Increased temperatures in March and April have an impact on the animals because this is the breeding season. The following table presents the total number of livestock in J&K during the 20th livestock census 2019

Table 1: Total number of livestock in J&K during the 20th livestock census 2019

| State | Cattle | Buffalo | Sheep | Goat | Total livestock |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 2539240 | 690829 | 3247503 | 1730218 | 8325324 |

Climate change has drastically reduced the welfare of animals. The global temperature has a negative impact on the production and reproduction of animals. In fact, heat stress reduces dry matter intake and causes oxidative stress in animals which leads to reduced production and fertility of animals. The increasing temperature during transportation has led to the increasing mortality rate of livestock. In general, an increase in temperature has led to both direct and indirect impacts on the livestock of Gujjars and Bakarwals. Direct effect on production and reproduction, increase in stress level by increasing cortisol, which depresses the ovarian hormone (FSH, LH) increasing consumption rate which decreases in kidding (newborn of a goat) and lambing (sheep) rate. The resultant effect is that this leads to a decrease in their livestock population. The indirect effect is on feed, and fodder which leads to a decrease in production. Climate change impacts horticulture and forestry. The goat is the top feeder (browser) and eats tree leaves only.

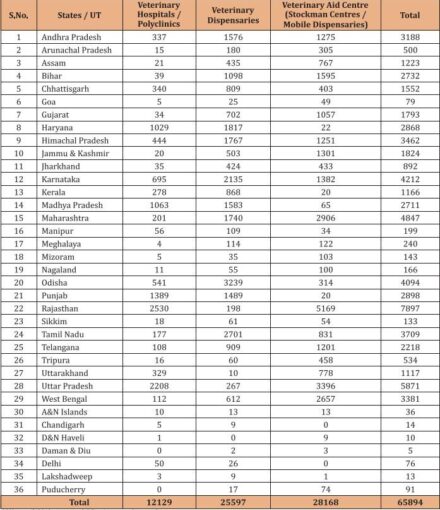

Due to an unusual rise in daily temperature in Jammu and Kashmir, the Gujjar and Bakarwal tribes began their seasonal migration to the upper reaches of the Himalayas one month ahead of schedule in 2009. However, the season changed and they were trapped in the mountainous range of Himalaya, where unseasonal snowfall continued for two weeks, killing more than 50 people and killing lakhs of animals. The problem is further aggravated by the rising trend of urbanization in Jammu and Kashmir hampering their traditional migration routes. The government does not also provide veterinary support to the livestock of Gujjars and Bakarwals. Table 2 shows the state-wise number of veterinary institutions (as of 31/03/2019). Their economy is entirely based on livestock, which has been devastated by the region’s droughts, unseasonal snowfall, and other climate-related issues. The issue of climate-related displacement in Kashmir poses serious threats to the Gujjar and Bakarwal societal sustainability.

Table 2: State-wise number of veterinary institutions (as of 31/03/2019)

Source: Annual Report 2020-21, Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying

The availability of water sources, as well as livestock production, are all affected by changes in rainfall. This has resulted in increased vulnerability in terms of food and water scarcity, with direct consequences for livestock, forcing the community to relocate early to summer pastures in the higher reaches of the Kashmir valley. Because residents of this area are already accustomed to extreme climate changes such as years without rain, severe droughts in summer pastures and winter pastures, and unseasonal snowfall such as in 2009, it is likely that this year will be no exception.

A survey is being carried out in Jammu and Kashmir’s Pirkimarg summer pasture. Many families have been surveyed to determine the total number of animals owned in the previous seven years. Lentho, a transhumant of the same pasture land, had 154 cattle in 2006, and 162 in 2007, but only 55 in 2009, indicating that more than 70% of the cattle died due to untimely snowfall.

Due to unseasonal snowfall, they became trapped in the upper reaches of Pir Panchal, Doda, Anantnag, Kulgam, Zojiala pass Jamia Gali, Pir Ki Marg, Chhapran, Upper Banihal, Wadwan, Trichhal, Mughal Road, Gurez, and Macheil sectors. Many respondents believe this is happening as a result of climate change. According to the Tribal Research and Cultural Foundation (TRCF), over three lakh to five lakh, nomadic Gujjars and Bakarwals were trapped in mountain ranges in 2009 while looking for pastures for their livestock during their seasonal migration, which began in April.

The availability and utilization of natural pastures is critical to the pastoral economy of Gujjars and Bakarwals. These pastures appear only at certain times of the year. As summer approaches, the lower reaches of the pastures dry up, while the upper reaches begin to thaw. As a result, a significant number of Gujjars and Bakarwals migrate from the lower Himalayan ranges to pastures in the upper Himalayan ranges. In their traditional meadows, 79 percent of respondents reported poor fodder quality and scarcity. They are dissatisfied with their pasture land, and as a result, the milk yield of the buffalo and the economy of the Gujjars and Bakarwals suffer, but they continue their transhumant adaptive activities in these areas. They rely on their buffalo herds and would like to relocate them to better pastures. However, resource depletion can be caused by overutilization. And we know that overuse is a direct result of rising human and animal populations. These pastures have been depleted as a result of overgrazing, and the cattle are unable to obtain sufficient quantities and quality grass to meet their needs. Furthermore, neither the forest department nor the graziers involved take any care to plant good quality grasses, nor is any attention paid to make up losses due to overgrazing, such as receding, which should be a permanent and regular feature of pasture development programmes.

Almost all of them believe that they are not safe in the hands of natural disasters. They faced a number of natural problems such as rain, snowfall, heavy storms, hailstorms, and landslides, which resulted in the loss of not only their loved ones but also their livestock. The unprecedented snowfall that lashed the entire Kashmir valley and parts of Jammu in June 2009 took a heavy toll on life and property. According to reports, approximately 25,000 cattle were killed, in addition to the destruction of hundreds of houses, the majority of which were migratory population huts.

Conclusion

Urgent policy intervention is required to address the impending issues of livelihood of Gujjar and Bakarwals. Development of grazing land with the help of forest department and cooperative societies should be a priority. A multi-stakeholders approach should be applied to mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change. This could be done by synergizing and converging policy parameters. Gujjars and Bakarwals need to follow the weather advisory broadcast by the meteorological department to avoid major losses of livestock and human life. The government could also reach out to the community by training them on how to face and mitigate the effects of climate change.

References:

- https://dahd.nic.in/sites/default/filess/Annual%20Report%202020-21%20%28English%2 9_30.06.21%5D.pdf

- https://www.greaterkashmir.com/todays-paper/op-ed/the-miseries-of-nomadic-tribes

- https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jestft/papers/vol8-issue1/Version-1/H08114146.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bakarwal#:~:text=The%20Gujjars%20are%20known%20b y,sub%2Dcaste%20and%20racial%20identity.

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/Jammu-and-Kashmir-Gujjars-Baker wals-advance-seasonal-migration-by-a-month/article16625615.ece

- https://www.thepharmajournal.com/archives/2018/vol7issue4/PartR/7-4-94-414.pdf

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.