These days, the term ‘environmental refugees’ frequently appears in global environmental summits, conventions, and discussions. It highlights the vulnerability of certain groups, emphasizing their loss of land, livelihoods, and the survival crises they face. This raises the question: how does such a crisis emerge in the first place? In recent decades, we have witnessed the rapid disappearance of coastlines, rising sea levels, increasing floods, intensified desertification, shrinking snow cover in circumpolar regions, and rising global temperatures. Against this backdrop, this article aims to examine the issue of environmental refugees, exploring its causes, consequences, and potential solutions.

Understanding Environmental Refugees: Definition and Impact

Large-scale expulsions of populations, forced to flee their homes for various reasons such as political violence, ethnic and religious conflicts, economic instability, and natural disasters, have been a part of migration history. However, the concept of environmental refugees is relatively new. The term ‘environmental refugees’ was coined by El-Hinnawi, who describes them as “people who have been forced to leave their traditional habitat, temporarily or permanently, because of marked environmental disruption that jeopardized their existence and/or seriously affected the quality of their life.” In simpler terms, environmental refugees refer to individuals displaced due to environmental crises.

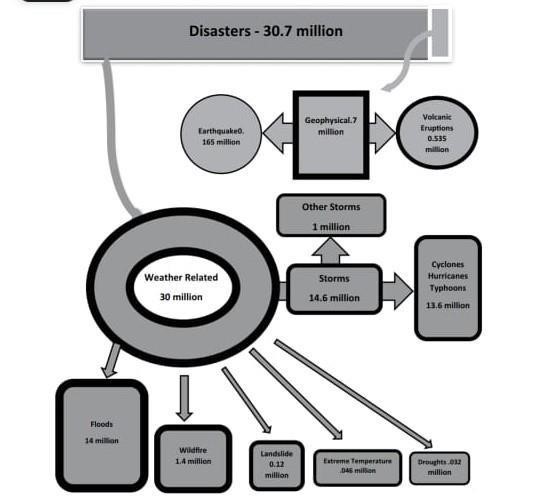

Environmental refugees are generally categorized into two groups: those displaced by natural disasters or elemental disruptions, and those displaced by long-term environmental degradation or biological disruptions. Human activities such as deforestation, over-cultivation, and overgrazing have increased the susceptibility to natural disasters like floods, droughts, and landslides, leading to the forced displacement of millions of people. For example, the 2014 floods in Jammu & Kashmir displaced around 812,000 people in the state’s urban areas. Similarly, Cyclone Bulbul, which struck the Sundarbans in 2019, caused 186,000 displacements. Furthermore, in 2020, Cyclone Amphan triggered nearly 5 million displacements across Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, and Bhutan, making it the largest displacement event of the year. In fact, 2020 was the worst year on record for internal displacements, with three-quarters of them related to extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, and storms, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). The figure below illustrates the internal displacements caused by natural disasters in 2020. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, in the early months of 2021, over 30% of those relocated were due to droughts.

Figure 1: Internal Displacements by Disasters in 2020

Source: Prepared using data collated from IDMC, GRID 2021, 2021 Global report on internal displacement (internal-displacement.org)

When examining the environmental refugee crisis, it is crucial to consider the long-term factors that contribute to environmental degradation and eventually lead to displacement. Numerous factors are responsible for displacement caused by long-term environmental degradation. These include the depletion of biological diversity (e.g., the decline in fish populations forcing marine fisheries to relocate), severe air and water contamination, global warming, rising sea levels, and climate change. The Earth has experienced its largest and fastest warming trend in the last century, with temperatures increasing by 0.74 degrees Celsius. This global temperature rise has led to the melting of glaciers, causing sea levels to rise and triggering floods. Rising sea levels particularly threaten small island states and low-lying coastal areas. In cases of glacial lake flooding, such as in the Himalayan region, forced relocation becomes the only viable option. Research suggests that by 2100, sea-level rise alone could displace millions of people. Additionally, deforestation and land degradation also contribute to outmigration. Many Scheduled Tribes in India have relocated to urban areas because deforestation and commercial land use have restricted their access to forest resources. A relevant example is the Indian state of Punjab, where land degradation due to intensive farming has led to significant outmigration.

According to the 2023 report State of India’s Environment in Figures, India recorded the fourth-highest climate-induced internal migration in the world last year. In 2022, as many as 2.5 million people were internally displaced due to climate-related disasters. The data shows that the country experienced extreme weather events on 314 days in 2022. The northwest region, which includes Punjab, Haryana, and Delhi, registered the highest number of extreme weather events, reporting such occurrences on 237 days. These outcomes are the result of a complex range of factors and their associated consequences.

Global Impact, Humanitarian, and Socio-Economic Consequences

The report “Costs of Climate Inaction: Displacement and Distress Migration,” which examines climate-related migration and displacement in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and other South Asian nations, presents a startling estimate: by 2050, more than 60 million people in the region could be homeless or displaced. This alarming figure highlights that climate change can no longer be ignored as a major driver of displacement. The estimated number is nearly as high as the global population displaced by war and conflict.

Conflict between the developed world, or the Global North, and the developing world, or the Global South, is inevitable due to the influx of environmentally induced displacement from the South to the North. The Climate Risk Index 2021 highlights that while the effects of climate change are being felt globally, emerging nations are disproportionately affected. Climate change is more likely to impact poorer nations and environmentally fragile regions, such as low-lying states.

Environmentally induced displacement often becomes a source of conflict between affected communities and the host countries. Refugees can exacerbate military challenges, heighten racial tensions, and ignite internal political unrest, especially among already marginalized populations. Additionally, the arrival of displaced communities creates competition for scarce resources, which can fuel economic distortions and hinder efforts by impoverished nations to escape poverty. Public expenditure is one example of this strain. In Gedaref, Sudan, for instance, local government employees are believed to spend up to 60% of their time addressing refugee-related issues. Migrants can also contribute to environmental degradation in host countries, as seen in the case of the recent influx of refugees from Rwanda into Zaire.

There may be a complex nexus between environmental and socio-economic factors that drives displacement. Climate change-induced migration has far-reaching social, political, and economic repercussions. While it does not directly trigger conflict, it can alter the ethnic composition within and between states and sometimes intensify instability and clashes of interest, especially in situations of resource scarcity.

Legal and Policy Framework

Climate change and environmental degradation lead to both internal and international displacement. Environmental refugees are not recognized under the Geneva Convention of 1951 or by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and therefore do not have the same legal status in the international community as conventional refugees. The international refugee regime established by the 1951 Geneva Convention does not provide protection for those fleeing due to environmental reasons. Additionally, while the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) at the Rio Summit (Earth Summit) in 1992 and the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 were early global efforts to address climate change, they lack specific provisions regarding the social and human rights impacts of climate change, including migration. Generally, there are no global governance structures that address internal migration, as it is considered a matter of national sovereignty. The global refugee protection system continues to prioritize migration caused by conflict and persecution over environmental factors.

However, the International Committee of the Red Cross has developed guiding principles to address climate-induced migration. These principles cover all stages of displacement, from providing protection and humanitarian assistance to the displaced, to their return, resettlement, and reintegration.

Regarding policies on internal migration due to environmental crises, two nations—Sweden and Finland—have incorporated environmental migrants into their migration policies. Some other countries have established specific regulations allowing people from nations devastated by natural disasters or major upheavals to stay temporarily without the threat of deportation. While India has a robust climate action plan at both the national and subnational levels, it does not adequately address climate-induced migration as a central issue. Although migrants receive immediate relief and rehabilitation support following disasters, there is limited long-term institutional support for their needs.

A notable development is the recent adoption of the African Union (AU) Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa. The convention defines internally displaced persons as “individuals or groups who have been forced or obliged to flee or leave their homes or places of habitual residence, particularly due to armed conflict, generalized violence, human rights violations, or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border.” This convention explicitly acknowledges the potential for relocation due to climate change. The world needs a similar approach at the international level.

Potential Solutions and Mitigation Strategies

Climate-induced displacement, as discussed, could surpass conflict as a primary driver of displacement if political leaders fail to honor their commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in accordance with the Paris Agreement. Addressing this issue requires both financial resources and political will to build community resilience against climate change and slow-onset climatic disasters, including sea level rise, drought, poor harvests, and biodiversity loss. In response to the challenges posed by environmental displacement, scholars have proposed various legal and policy solutions. For instance, Sujatha Byravan and Sudhir Chella Rajan have suggested establishing a new global convention to provide special migration status for climate exiles and migrants. Meanwhile, Frank Biermann and Ingrid Boas advocate for the creation of a Climate Refugee Protection and Resettlement Fund. To address this urgent problem, the primary need is to legally recognize environmental refugees at both national and international levels. Additionally, source countries should identify high-risk areas and assess economic losses resulting from recurring hazardous weather events. They must also collaborate with governments and the private sector in destination countries to establish funded facilities, such as language schools, cultural centers, and trade schools, either at or near the source of displacement.

The recent report from ActionAid and its partners, Bread for the World and Climate Action Network South Asia, highlights the need for strong leadership and ambition from developed countries to cut emissions and support developing nations in adapting to climate change and recovering from climate disasters. The report calls on developing nations to enhance their efforts to protect people from the impacts of climate change and proposes a comprehensive strategy that places the responsibility on wealthy nations to provide assistance. It also stresses the importance of improving data on displacement caused by “slow-onset events, including drought, coastal erosion, sea level rise, salinization, glacial retreat, and permafrost melt,” and understanding how these phenomena interact with sudden-onset hazards to trigger displacement.

It is essential to implement a multi-pronged approach to address the adverse impacts of climate change, especially for underdeveloped and developing countries. While it is true that environmental-induced displacement is challenging to mitigate due to its varying impacts across different regions, the global community must recognize the urgency of this issue and take prompt and decisive measures to tackle and mitigate this humanitarian crisis.

References

-

-

-

-

http://www.jstor.org/stable/43953626

-

-

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40212341

-

http://www.jstor.org/stable/44519184

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.