Inclusion is grounded in the fundamental human right to education for all, as enshrined in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Quality inclusive education (IE) also constitutes a vital element of the new Sustainable Development Goal agenda. The overarching principle of the Sustainable Development Goals is to ‘leave no one behind.’ Unfortunately, children with disabilities remain one of the most marginalized groups, despite overall progress in global educational attainment. They are less likely to participate in and complete their education compared to their peers without disabilities. In South Asia, an estimated 29 million children were out of school in 2018 – 12.5 million in primary school and 16.5 million in lower secondary school. A significant proportion of these children were estimated to have disabilities, particularly in India.

The National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) of India has been hailed as ushering in a new era of educational reform. However, it operates within a framework of pervasive policy gaps in the education of disabled children. In India, inclusive education has been described as excluding children with disabilities. Disabled children rarely complete primary school, with only 9% completing secondary school. Approximately 45% of disabled people are illiterate, and only 62.9% of disabled people aged 3 to 35 have ever attended regular schools. Specific disability categories and genders are disproportionately affected. For instance, children with autism and cerebral palsy are less likely to be enrolled in school, as are girls with disabilities. In this paper, we examine the status of disabled children in education in India and the major roadblocks. India’s education system for the physically challenged is in serious jeopardy and requires concentrated efforts from all stakeholders.

Status of education among disabled children in India

A study by the World Bank (2007), based on NSS data, noted that children with disabilities are five times more likely to be out of school than children belonging to scheduled castes or scheduled tribes (SC or ST). Furthermore, when children with disabilities do attend school, they rarely progress beyond the primary level, resulting in lower employment opportunities and long-term income poverty. Even in states with high overall enrollment and good educational indicators, a significant proportion of out-of-school children are disabled: in Kerala, the figure is 27 percent, and in Tamil Nadu, it is more than 33 percent. Data also indicates that across all levels of severity, children with disabilities very rarely progress beyond primary school.

The 2019 “State of the Education Report for India: Children with Disabilities” considered the 2011 census, which indicated that there are 78,64,636 disabled children in India, constituting 1.7 percent of the total child population. Three-fourths of children with disabilities under the age of five and one-fourth between the ages of five and 19 do not attend any educational institution. The report noted that only 61 percent of children with disabilities (CWDs) aged 5 to 19 were enrolled in school, compared to 71 percent overall when all children are included. Moreover, 12% of children with disabilities have dropped out of school, and 27% have never attended any educational institution. According to the report, a large number of disabled children do not attend regular schools but instead opt for the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS). A review of NIOS enrollment figures also shows a drop in most categories of disabilities between 2009 and 2015.

The Unified District Information on School Education (UDISE) + data for 2018-19 also presents a grim picture. It highlights a persistent and almost static enrolment of children with disabilities over the years. In 2013-14, the enrollment of disabled children in school education was 1.1% of the total number of students enrolled. This figure declined to 0.9% in 2018-19. Gender disparity in the enrolment of girls with disabilities also persists.

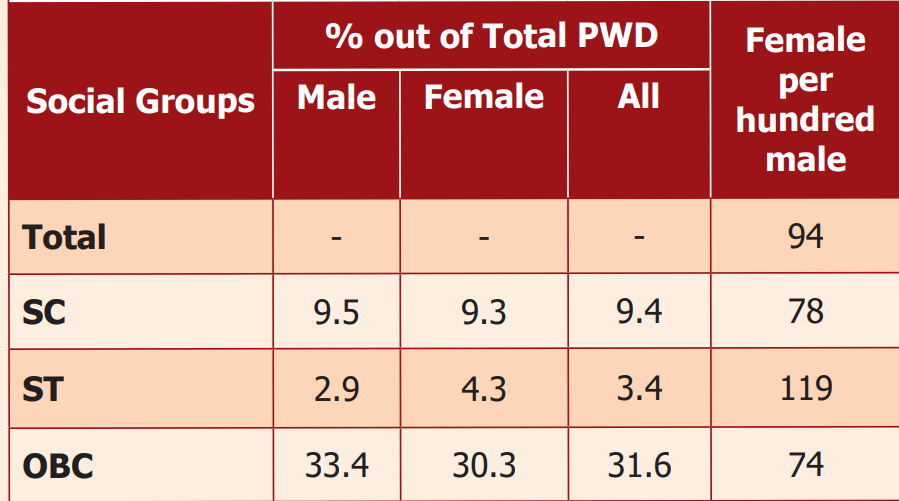

According to the AISHE report of 2020, the estimated state-wise total enrollment in higher education is 38.5 million, of which 92,831 PwD students were enrolled, as compared to 85,877 in 2019. Among these, 47,830 are male, and 45,001 are female students. When we compare this number with other disadvantaged groups, it is the least among all, clearly indicating that a very small number of these individuals pursue higher education. The table below illustrates the social group-wise distribution of PwD students.

Table: Social group-wise distribution of PWD students

Roadblocks to Education

The plight of disabled children is rooted in their inability to manipulate personal and environmental variables, thereby restricting the performance of daily tasks and disrupting established role patterns and social role expectations. The most significant roadblock for PwD students in education, particularly higher education, is the lack of awareness of government-run programs. This is evident in the 2011 census data, which shows that in rural areas, 49% of the disabled population is literate, while in urban areas, the percentage of literate individuals among the disabled population is 67%.

In the village surveys conducted by the World Bank in UP and TN, the team noted that 72.3 percent of households with disabilities were not aware of schemes for free aids and appliances. Instead, it is observed that “while assistive technologies are a right under the SSA, they are, in practice, rationed, making them a privilege.” It is evident that the benefit of the reservation made for PwD students is often violated, as even a person with a minute disability can obtain a disabled certificate and misuse it. In this way, many people are prevented from taking advantage of it due to a lack of awareness or not knowing the proper channel through which they can obtain this certificate.

A child’s access to preschool and primary education is most likely to be hampered by the lack of disabled-friendly institutions. According to members of the NCPEDP, less than 1% of the country’s total number of educational institutions are disabled-friendly. Many buildings are old, so the new norms don’t apply to them, making them fail to meet disabled-friendly standards. Children with autism and cerebral palsy, as well as disabled girls, are the least likely to be enrolled in school. Less than 40% of school buildings have ramps, and approximately 17% have accessible restrooms.

In the AISHE (2020) report, only ramps and separate toilets for females are surveyed, although that is not the only criteria to make the HEI accessible for PwD students. There should also be a survey conducted on the availability of lifts, elevators, inclusive toilets, restrooms, and hostel facilities for PwD students in all the HEI, as a person with a locomotor disability may need these amenities. Additionally, there is a shortage of trained special educators in mainstream schools.

The issue is further exacerbated by the attitude of other children, often manifesting as teasing and exclusion by peers. According to the UNESCO report, besides physical infrastructure, processes in the school, and essential resources like assistive and ICT technology and devices, the attitude of parents and teachers towards including children with disabilities in mainstream education is also crucial to achieving the objective of inclusive education. Most PwD students reside in rural areas where social stigma persists, with the belief that obtaining an education won’t necessarily benefit them in overcoming employment challenges. In rural India, it is observed that people, especially women, due to societal stigma, avoid disclosing the truth about disability. Mehrotra (2004) noted that rural women with disabilities may be the most likely to be overlooked.

A part of the problem also lies in the lack of inclusive policies. Existing laws governing education for people with disabilities are ambiguous. According to the 2016 Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, educational institutions must “provide reasonable accommodation according to the individual’s requirements and provide the necessary support, individualized or otherwise, in environments that maximize academic and social development consistent with the goal of full inclusion.” However, according to the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy review published in May 2020, the terms “reasonable accommodation,” “individualized support,” and “full inclusion” have not been defined, leaving room for arbitrary implementation.

Recommendations

Measures are required to ensure quality education for every child to meet the goals and targets of Agenda 2030, specifically Sustainable Development Goal 4. Disabled-friendly infrastructure, such as ramps, lifts, elevators, inclusive toilets, and hostel facilities, should be the government of India’s priority. Most PwD individuals live in rural areas, for whom a proper awareness program concerning opportunities, employability, scholarship schemes, disabled certificates, and various other important matters should be organized. These programs can address doubts and social stigma effectively.

Various national portals can be useful for PwD students, such as www.swavlambancard.gov.in for unique ID cards, disabilityaairs.gov.in for various schemes, disabled certificate forms, and scholarship-related information (www.nhfdc.nic.in, www.india.gov.in, thenationaltrust.gov.in, etc.). These topics should be discussed in orientation programs to guide students on how to use these resources. Moreover, every educational institution should have an accessible support centre for PWD students. The implementation and regular follow-up of programs should be monitored.

The government should also focus on curriculum transformation and adopting teaching practices to aid the inclusion of diverse learners. Additionally, it should establish a coordinating mechanism under the HRD Ministry for the effective convergence of all education programs for children with disabilities. Ensuring specific and adequate financial allocation in education budgets to meet the learning needs of children with disabilities is crucial.

One of the main challenges is the unavailability of reliable data, as many relevant global and national indicators need to be disaggregated by disability status. The lack of research that compares the outcomes of education for people with disabilities navigating different education systems – mainstream, special, and home schools – continues to be a hurdle in designing inclusive policies. As the government invests significant amounts of money into disabled-friendly infrastructure, research must be conducted to establish the effectiveness of these efforts.

India needs to prioritize the adoption of standard criteria in data collection. To ensure inclusive societies, concrete action is required to make persons with disabilities and their situations visible in policymaking. Robust data and analysis are required to ensure that persons with disabilities occupy their rightful place in the SDG framework and its implementation, monitoring, and evaluation.

Conclusion

The participation of disabled children in education is meagre. A gap remains in the enrollment and retention of disabled children in education despite government schemes and programs like Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), Integrated Education for Disabled Children, Right to Education (RTE) Act, and Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act. Major roadblocks to education include a rigid curriculum, inaccessible infrastructure, the absence of modified assessments, lack of awareness, and social stigma. Part of the problem also stems from the unavailability of reliable data required to design inclusive policies.

The article concludes that to ensure rehabilitation, empowerment, and the overall development of PwDs, disability needs to be mainstreamed into the implementation plan of SDGs, and national development programs need to prioritize inclusive development. We must overcome stereotypes and foster positive attitudes toward children with disabilities in the classroom and beyond. It should and will be our objective to make mainstream education not just available but accessible, affordable, and appropriate for students with disabilities, ensuring that “No One is Left Behind.”

References:

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.